The Color of Dedication

Stage three-and-a-half means "yellow," and yellow means "go, go, go" in the banana world.

If you’ve worked in a produce department, you know stage three-and-a-half very well. Beneath the lid of a banana box, fruit that’s "breaking" yellow with a strong hint of green is satisfying, encouraging to produce staff. It means the fruit has shelf life, so you can pile the bananas high and watch them fly out the door. Stage five (yellow with brown spots) is perfectly ripe, and, therefore, too far gone for retail. Stage 2 (grass green) slows sales. Produce buyers and managers love stage three-and-a-half.

That’s because customers love it, too. Who doesn’t want a perfect banana?

So obsessed are we with perfection where bananas are concerned that we’ve fashioned a maddeningly efficient industry designed to hit that "go" color of yellow—from tropical factory banana plantations employing intense pesticides and fungicides to mechanized packing houses to refrigerated ships that transport bananas at exactly 58 degrees Fahrenheit to climate-controlled ripening rooms. Consequently, we have an incessant, relentless river of bananas, one that transports 37 billion pounds of bananas across the globe each year, over half of which are consumed in the "First World," that is, Europe and America.

But it’s important to remember that developing countries produce 98 percent of those 37 billion pounds yet receive only a sliver of the $7 billion–$8 billion receipts generated by the international banana industry. Not surprisingly, the tension between these regions and U.S. banana/fruit cor-porations is severe—and many generations old, too. The Spanish-American War of 1899 ignited 40 years of war and occupation in Panama, Honduras, Guatemala, Colombia, and Nicaragua in order to ensure that Standard Fruit (now Dole) and United Fruit (now Chiquita) could safely industrialize these tropical fruit regions without resistance from local governments.

First World supremacy over banana regions is reinforced to this day.

The 2009 coup in Honduras was sparked to protect the United States’ dominating investments in the country, according to Manuel Zelaya, the president who was forced from power. Chiquita and Dole Foods are both noted for busting unions and allegedly killing organizers in Central and South America; and these two companies, which together make up over 25 percent of the international banana trade, have been sued for funding paramilitary organizations that kill farmers or force them off their land.

The price paid by farmers and union organizers is high, but it keeps the fruit conglomerates in control. It also keeps the First World in a daily supply of perfect, yellow bananas.

Brand new bag

It’s easy to wish for a different, less-bloody model, but changing the flow of the relentless river that began flowing more than a century ago would be impossible.

But might we create a way to work around that river, one that helps people instead of hurting them?

For Bradley Russell of Equal Exchange, who’s working hard to create a different kind of fruit program, even that task is easier said than done. In fact, it’s a minor miracle if she doesn’t spend her day in crisis mode, working to bring fairly traded bananas into the United States.

"We can’t usually do the things we’d love to do, like marketing and other projects," Russell said, laughing. "We’re scrambling all the time to get fruit to our customers."

Equal Exchange was an early fair trade pioneer, bringing coffee to the U.S. by cooperating with Nicaraguan growers in the ’80. It’s a business model that puts power in the hands of small farmers who otherwise don’t have the means to compete on a global, corporate scale. By partnering with small banana growers cooperatively rather than overpowering them, Equal Exchange Banana Operations is attempting to create a new path for bringing bananas to the First World by empowering the fruit growers. For example, El Guabo Co-op in Ecuador, a cooperative of small banana farms, owns a significant share of the Fair Trade fruit company Agrofair, which in turn has an ownership stake in Equal Exchange’s Banana Program. Russell says this makes all the difference in changing how banana business is conducted.

"The farmers have a stake in seeing our [Equal Exchange Banana] program survive," Russell said. "That completely changes everything by giving those farmers ownership over its success."

It may change everything politically, but the trick of shipping bananas from the equator to North American retailers is elaborate as it ever was for Equal Exchange Banana Operations.

Come, Mr. Tallyman

Indeed, it’s actually harder for Equal Exchange since they have far less money than a giant food corporation, and, as a result, nearly every step of the co-op’s banana supply chain has been reinvented in shoestring, DIY fashion.

When Russell, whose office is in Boston, places an order directly with El Guabo Co-op in Ecuador, the farmers themselves harvest, cut, wash, sticker, and pack the bananas, all in a single day. There’s no mechanization involved. Oftentimes, the packing of bananas into boxes is done in the middle of the farmers’ own homes.

The farmers then haul their boxes to a centro de acopio, a central staging area owned by El Guabo, where 40,000 pounds of boxed bananas are placed in a refrigerated container, trucked to the port city of Guayaquil, Ecuador, and loaded onto cargo ships.

This in itself is a key difference between Equal Exchange and the big fruit cor-porations, who own their own ships designed specifically to transport bananas from their own gigantic ports. (Dole owns a port called "Banapuerto" in Ecuador so huge that a year’s worth of Equal Exchange bananas would take up less than half its holding space.) Meanwhile, Equal Exchange must load onto private cargo ships designed to carry anything—not just bananas. "These are less efficient than banana boats and, therefore, more expensive for us to use," Russell said.

Eleven days after being loaded, the cargo ship arrives in New Jersey where the bananas go through inspection at customs. Once released, the bananas are loaded onto refrigerated trucks and hauled to customers, such as J&J Distributing in Minneapolis, which own "ripening rooms." Here the bananas are taken off refrigeration and allowed to begin ripening.

It all goes according to plan 80 percent of the time, says Russell, so that stores see the "go" color when they order Equal Exchange bananas. But sometimes green is the only option. Green bananas demoralize produce managers, regardless of the brand, since green can make some customers turn on their heels and walk out the door. Why are there days, even weeks, when bananas are grass green?

Green means unripe bananas had to be released to fill your order because, somewhere upstream, supply was suspended, hung up. When creating do-it-yourself, banana bucket brigades that span continents, stuff happens, as they say. Trucks flip over, spilling thousands of pounds of bananas across a mountain road, cranes on cargo ships stop working and farmers are told to stop harvesting, or customs inspectors find unidentifiable insects in banana shipments, all of which cause hair-pulling delays for the Equal Exchange Banana Operations team. Fruit corporations have fleets of banana boats and armies of trucks for just such emergencies—not so for Equal Exchange. But Russell seems undaunted by setbacks, keeping squarely in mind her reasons for dealing with all these hassles and why they might be worth it.

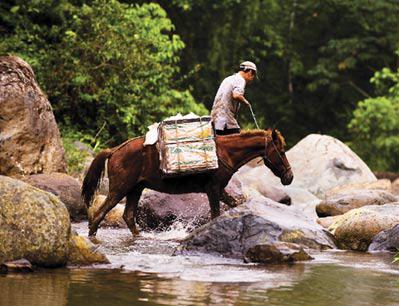

"We work with 450 small farmers [in Ecuador]," she said. "Some of them are literally taking their fruit down the mountain by mule-back. We don’t even know their logistical problems or how much stuff the farmers deal with before putting [their bananas] in a box."

When you see stage three-and-a-half, yellow bananas arrive in your store, it means the fruit didn’t get quarantined at customs, the cargo cranes didn’t break, refrigeration didn’t fail, the banana truck didn’t crash, and the mule’s back held.

"They may be green as a Paddy’s Day parade," Russell said. "But they still came from a small farmer. It just takes a little more time on the consumer’s end to ripen them."

That river of 37 billion pounds of bananas per year shipped globally is an elaborate trick. But it’s more accurately called an illusion, one that hides real pain and damage in communities where those bananas were grown.

This is an illusion too: A never-ending supply of perfect bananas. For a different model to work, retailers and customers are going to have to dedicate themselves to the co-ops that hauled those bananas to market and to resist the allure of jumping to perfect yellow-with-green corporate bananas. Eighty percent of the time, Equal Exchange bananas are breaking yellow, perfect. But where cooperating banana farmers are concerned, we have to change the expectation that green means "stop buying." Green Fair Trade bananas should mean, "Step up for farmers, co-op shopper." This grower upheld her half of the bargain, getting this fruit cut and packed for us, and Bradley Russell and the Banana Operations team executed their astonishing end-run around the banana industry to get it here, hounding the bananas all their way from South America to our stores.

For small banana farmers, green means go.