Cuban Meeting Ground

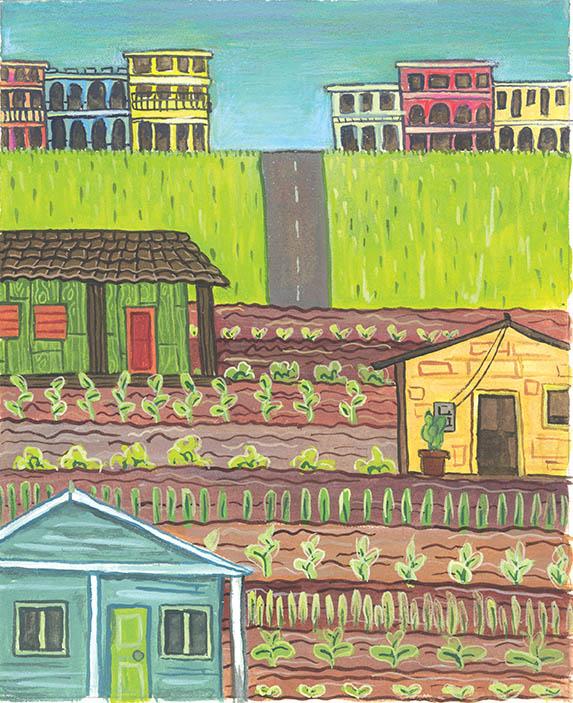

Cuba is opening not only to more visitors but also to more cooperatives.Its food economy is shifting from centralized practices of the past to rapid cooperative development.

Now imagine a Cuban–North American dialogue that asks: “What do you bring?”

The questioner could point to widespread poverty, degraded infrastructure, mediocre public health statistics, environmental pollution, and destructive food production practices—referring to the U.S., of course. A Cuban might ask, “What can we learn from that?”

On the other hand, “What do you bring?” is a very different question coming from people in the U.S. and Canada. By improving relations with our Caribbean neighbor, we will not only increase beneficial trade. There also is much to be learned, and if we ask from the point of view of co-op development and intensive food production, the potential is impressive.

Cuba’s new wave of co-op development is through producer and worker cooperatives. North American worker cooperatives, an underdeveloped sector (Quebec excepted), can share lessons with Cuba while also learning. The present issue’s report on Cuba’s cooperative transition mentions that Saint Mary’s University in Halifax—home of the degree program for Master of Management, Co-operatives and Credit Unions—is engaged in sharing Co-op Index, an evaluation tool, with Cuban cooperatives. And for updates from U.S. co-ops, see: http://www.ncba.coop/us-cuba-about.

Past and future

In case any readers don’t recall the background, here are 1960 remarks by soon-to-be-President John F. Kennedy, softened for his U.S. audience:

At the beginning of 1959 United States companies owned about 40 percent of the Cuban sugar lands—almost all the cattle ranches—90 percent of the mines and mineral concessions—80 percent of the utilities—practically all the oil industry—and supplied two-thirds of Cuba’s imports. Of course, our private investment did much to help Cuba. But our action too often gave the impression that this country was more interested in taking money from the Cuban people than in helping them build a strong and diversified economy of their own.

The U.S. failed to reverse that “impression” and soon sponsored a failed invasion, then numerous attempted assassinations and subversions, plus the trade embargo.

Nevertheless, “Cuba’s internationalism continues,” notes Canadian author Susan Babbitt (at counterpunch.org):

Cuba began exporting doctors in 1963... After Hurricanes George and Mitch devastated Haiti, Honduras, and Guatemala in 1998, Cuba sent 2,000 doctors and other health professionals,…Cubans willing and able to work where no health services previously existed. After Hurricane Katrina, Cuba offered to send, at no cost, 1,586 medical personnel and 36 tons of emergency medical supplies to the United States, an offer that was turned down.

In 2014, the Wall Street Journal reported that “Few have heeded the call [to fight ebola], but one country has responded in strength: Cuba.” Cuba responded without hesitation, sending more than 450 doctors and nurses, chosen from more than 15,000 volunteers, by far the largest medical mission sent by any country.

The new direction for cooperatives and relations with Cuba is positive and exciting. Yet the punishing U.S. embargo continues. Cuba’s example matters greatly, as it has in the past, both for its resistance to U.S. corporate and military domination and for its model of shared wealth under stressful circumstances. These are lessons for the world, including cooperators in North America.

Poet Richard Blanco, who promotes dialogue at BridgestoCuba.com, is cautious (NYT interview, 7/28/15):

Many of us who might have visited Cuba or have imagined visiting Cuba think of it nostalgically.

[Blanco:] It’s somewhat of an annoying question to me, because it lacks sensitivity. For Americans, Cuba has a psychic hold on the imagination, but we have to understand Cuba is a real country with real people. Cuban people don’t exist to entertain our romantic notions of them, past, present or future.

Nevertheless, the question of wealth sharing is foremost, and there is no country in greater need of more fair wealth distribution than the U.S. Cooperatives are a means toward that end.

North Americans can help build cooperation and ensure that there is no return to hostile relations. We can support Cuba friendship and urge an end to the cruel and self-destructive Cuban embargo.

Both countries have a future of potentially enormous growth in cooperative impact. But only in Cuba is growth in cooperatives a shared national goal. ♦