The Co-op that Changed the South

It was a small cooperative store on a little-known island off the coast of South Carolina. During the harshest days of the civil rights struggle, embattled black leaders came through its doors seeking inspiration. Among the legendary leaders who visited the co-op were Ralph Abernathy, Dorothy Cotton, Conrad Brown, Fannie Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Bernice Reagon, Cleveland Sellers, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), Andrew Young, Hosea Williams, and many others.

The co-op was called the Progressive Club. Johns Island is one of the Sea Islands, home to the unique Gullah people who had retained a lot of their African cultural heritage. In the 1940s, Johns Island was remote and a nine-hour ferry ride to Charleston, S.C. After WWII, bridges slowly began to connect Johns Island to the mainland.

What began in that co-op was a Citizenship School to teach blacks on Johns Island how to qualify to vote. Later, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) spread that program throughout the South. That one class in the co-op became thousands of classes in churches, schools, and homes. In 1962, the SCLC brought in other groups that then formed the Voter Education Project (VEP). Between 1962 and 1966, VEP trained 10,000 teachers for Citizenship Schools, and 700,000 black voters registered throughout the South. By 1970, another million black voters had registered.

Aldon Morris in his book Origins of the Civil Rights Movement wrote: “…the Citizenship Schools were one of the most effective tools of the movement.” That class at the co-op led to millions of blacks voting for the first time, and as a result, the South and U.S. history were changed.

Mutual aid in 1948

The Progressive Club was started in 1948 by Esau Jenkins and other Johns Island residents as both a consumer co-op and a mutual-aid organization. About 40 families started the co-op. The co-op bought an old school building on River Road and sold everything from groceries to gasoline and seed to feed. The members used it to trade goods and services and as a mutual-aid program to help each other in time of need. Every member of the Progressive Club had to be a registered voter and had to pledge to get one or more voters out to vote on Election Day. A little later, Jenkins and others organized the CO Federal Credit Union (still operating) to serve low-income blacks who could not otherwise get mortgages or loans.

In his business life, Jenkins ran a bus service that served the needs of high school students and daily workers going from the island to downtown Charleston. One day in the 1950s, one of the passengers, Alice Wine, said to Jenkins, “I’d like to hold up my head like other people, I’d like to be able to vote. Esau, if you’ll help me a little when you have the time, I’d be glad to learn the laws and get qualified to vote. If I do, I promise you I’ll register and I’ll vote.”

Jenkins heard her plea. Blacks could not get the vote in South Carolina unless they could pass the literacy test. He copied off the laws and handed them out to his passengers. He began a daily custom of teaching them how to read and write and learn the law while he drove the bus. Alice Wine was the first of his passengers to register to vote. What Jenkins was teaching on the bus to a few passengers, he wanted to make available to all the disenfranchised blacks on the Sea Islands. But how?

Another avenue for Jenkins’s road to democracy was about to be opened by Septima Clark. In 1953 Clark, an activist Charleston teacher, learned about the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, one of the few places in the South where blacks and whites could meet together. The Highlander Center was modeled after the Danish Folk Schools, which themselves spurred the Danish cooperative movement.

Clark had taught on Johns Island, and Jenkins had been one of her students. In 1954, Clark went twice to the Highlander Center. There she met the founder Myles Horton and his wife Zilphia, who that summer came down to Johns Island to learn about what was going on.

In 1955–56, Clark taught a leadership class at Highlander. She used her car to transport three groups of people there from the Charleston area, including Jenkins. During his time at Highlander, Jenkins saw that a combination of the Highlander teaching technique and his rolling bus classroom was the next step. Jenkins saw also that Clark was an exceptional teacher of the Highlander method. Propitiously, Bernice Robinson, a cousin of Clark, was another of the Charleston attendees. Jenkins asked Highlander to help merge the two formats and sponsor a Citizenship School on Johns Island.

Citizenship School grows

The first form of the Citizenship School began at the Progressive Club in 1957. But with the co-op having grown to 400 members, the old school building could not also accommodate the growing needs of the Citizenship School. They tried to rent, but none of the schools, churches, or organizations on Johns Island dared to let the Citizenship School use their buildings. They were afraid of what might happen to them.

Jenkins and the members of the Progressive Club saw that the only option was to do it themselves by buying land and building a new co-op store with meetings rooms. Jenkins called Horton at Highlander to talk about where the Progressive Club would get the funds.

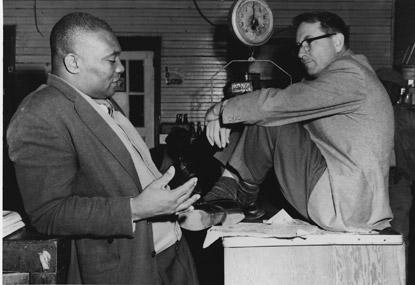

Highlander lent the funds to the Progressive Club to buy land on Johns Island to build a new larger co-op store. The new store was built nearby on River Road and opened in 1963. (The building still exists and is now on the National Register of Historic Places.) At the front of the co-op’s building was the retail shop, with a storeroom behind it that acted at night as a meeting room. Behind that, they built a dormitory to house participants from afar and also constructed an indoor basketball court. There, amongst the weighing scales and storage counters, democracy for many blacks in the South was born. Alice Wine became one of the cashiers at the co-op, and she can be seen in a lot of the historic photos.

Septima Clark is one of the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. (In 1955, she invited Rosa Parks to her class at Highlander, just months before Parks refused to give up her seat on that bus in Montgomery, Ala.). In 1955, the state of South Carolina passed a law stating that teachers who were members of the NAACP would not be allowed to keep their jobs. Clark would not leave the NAACP, and in 1956 she lost her teaching job in Charleston. Horton learned that Clark had been fired and asked her to become director of workshops at Highlander as well as the Highlander’s liaison with Jenkins and the Citizenship School.

In Ready from Within, Clark comments about the co-op store, “...Esau’s group fixed the front part like a grocery store and sold things to themselves…There were two rooms in the back, and in those two rooms we taught. We didn’t want white people to know we had a school back there. We didn’t have any windows…”

Brought in to be the regular teacher at the Progressive Club was Robinson, the young cousin of Clark who had also attended Highlander. Highlander raised funds to pay for the program and had Clark oversee it. Soon the Marshall Field Foundation in Chicago took an interest in growing the program beyond Johns Island.

However, at this time the state of Tennessee decided to use illegal tactics against Highlander. As a result, Highlander was closed and all its properties and assets sold by the local sheriff at auction. To protect the Field grant and the Citizenship School program, the Highlander quickly transferred the funds and the program to the SCLC. Clark, Robinson, and others were transferred with it. Andrew Young and Dorothy Cotton were asked by the SCLC to grow the program beyond Johns Island to the rest of the South.

Young and Cotton and many other civil rights leaders still visited the Progressive Club to see how the program best worked. On her way back from a visit to the Citizenship School with other Mississippi voting rights activists, Fannie Lou Hamer was infamously beaten up in Winona, Miss.

We shall overcome

There are many other stories about the impact of the Progressive Club and the Sea Island Folk Festival that took place in the field behind the Progressive Club. Intertwined with all of this is the work of Guy and Candy Carawan of the Highlander Center, who lived on Johns Island in 1963. Carawan spread an old song from South Carolina through the Highlander Center to Pete Seeger and the rest of the world. That song, “We Shall Overcome,” is now a freedom anthem worldwide, and the song rights are owned by the Highlander Center.

“We Shall Overcome” reminds us of the accomplishments of that simple Citizenship School, humbly created in a co-op shop, that became one of the greatest stories of the civil rights movement.