Building Board Capacity to Lead

Imagine that your co-op’s board of directors simply disappeared for a year or two. What would happen? Certainly, the absence of a functioning board would violate a key legal requirement for a cooperative business. Members would also lose an important point of connection to their co-ops and one avenue to raise questions and concerns. And the risk of errors, oversights, and poor performance could rise if management stopped reporting to a governing body.

But how would the absence of the board impact the co-op’s strategic direction or leadership culture? Would it deprive the co-op of a source of critical thinking, diverse perspectives, or keen insights into the organization and the environment in which it operates? If the answer is “probably not” or “no,” what does this say about the value and consequence of the board’s leadership role?

A problem of purpose

This provocative inquiry is at the heart of Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards (2005), by Richard P. Chait, William P. Ryan, and Barbara E. Taylor. The authors start with the observation that many directors of nonprofit boards do not perceive deep value in their work. Chait et al. identify this as less a problem of board performance than a problem of uncertain or limited purpose.

In their view, directors are justified in feeling that the scope of their work is too narrow, because it often is: The majority of boards do not regularly bring the kind of discernment and critical thinking to their governance that is not only intellectually engaging, but can also create unique value to the organization.As a remedy, the authors suggest reframing the board’s work to extend beyond familiar modes of governance, in a way that fosters directors’ ability to serve as thought leaders who are able to ask catalytic questions, frame problems, and grapple with complexity.

The authors’ focus is nonprofit boards, but in my observation cooperative boards of directors are similarly not immune from wondering about the purpose and value of their work. For some, at least, co-op board work can seem to consist primarily of evaluating monitoring reports and other routine matters, punctuated by an occasional “coffee with the board” and a conversation about the Ends policies at the annual retreat. Episodic work—overseeing an expansion or hiring a new general manager—is much weightier, but infrequent. For boards stuck in a bit of a governance rut, as well as high performers on the lookout for fresh ideas, Chait et al.’s multimodal governance model, described below, might be just the thing to inject a jolt of new energy and critical thinking into the boardroom.

Multimodal governance at a glance

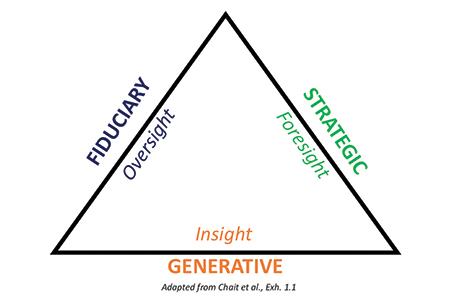

The authors’ conceptual model identifies three distinct governing modes, each of which a board must attend to and master if it wants to do an outstanding job of governance:

In the fiduciary mode, a board fulfills its duty to safeguard assets, set performance expectations, establish policy, oversee financial and operational performance, and ensure legal and regulatory compliance. The board’s primary function in this mode is to exercise oversight, in its role as steward. The work is bureaucratic in nature and views problems as something to be identified. This mode is a familiar one to most, as it is where many boards spend the bulk of their time.

In the strategic mode, the board, in partnership with the CEO or general manager, makes major decisions to ensure the organization is positioned for success, including setting the organization’s direction, evaluating plans and priorities to move in that direction, and deploying resources accordingly. Perpetuating leadership that can serve the organization’s current and future needs is another key strategic activity. The board’s primary function in this mode is to exercise foresight, in its role as strategist. This work is analytical in nature, and views problems as something to be solved.

In the generative mode, the board, again in collaboration with the CEO or general manager, engages in a cognitive process to decide what to pay attention to, what it means, and what to do about it. The board’s central purpose in this mode is to develop insight in its role as a sense-maker. Generative work is non-linear and non-rational in nature, embraces divergent viewpoints, questions assumptions, and views problems as something to be framed. When working in this mode, a board functions as a sort of think tank, with parliamentary procedure suspended amid conversations that are looser and more free-flowing.

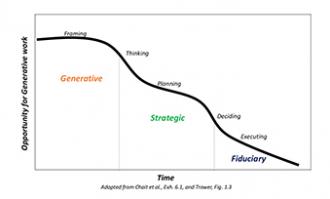

The authors offer several ways to visualize how these three modes relate to one another:

1. They can be seen as legs of an equilateral triangle, reflecting that all modes are equally important to effective governance.

2. On many issues, a board will move through each mode sequentially over time, with the opportunity for generative work decreasing as a group moves closer to a decision point. Imagine, for instance, a co-op contemplating the possibility of future growth. Initially, a board might engage in generative thinking around philosophies of growth and their implications, with lots of learning, analyzing the Ends or mission, consulting multiple perspectives, and framing the issues. As time passes and priorities begin to emerge, the general manager will begin working to develop a formal plan. Working actively with the general manager, the board will shift to strategic mode to weigh specific proposed actions, engage with members to build alignment, and eventually make a decision whether to move forward. Once the project is underway, the board’s primary mode will be fiduciary, as it hears reports from the general manager on progress and the budget, and eventually on operational performance in the expanded business.

3. Finally, the modes can be visualized as a triple helix, with each mode as a distinct yet interwoven thread. This reflects that sometimes a group might engage in all three modes simultaneously. Consider, for example, a board that decides to take a deeper dive on the annual meeting plan. In its fiduciary capacity, the group would consider things such as the budget, statutory requirements, and procedures to ensure a fair election. In the strategic mode, conversations might center on ways that the meeting could support organizational goals, such as providing a platform to announce a new initiative or educating members on a key topic. Throughout the process, the board might engage in generative thinking on how co-ops should express their democratic nature, what that looks like to different stakeholders, and whether/how an annual meeting is a good vehicle for achieving those goals.

Most people find the generative mode the most intriguing, likely because it is the most unfamiliar, and because it offers the promise of a disciplined way to pursue more engaging and consequential board work. If you fall into that camp, then read on for some suggestions about how to get started.

But first, a point of clarification: Multimodal governance is entirely consistent with the Four Pillars of Cooperative Governance¹ , and it is not a replacement for Policy Governance or any other system that the board uses for empowerment and accountability of the co-op’s general manager or the board itself. It is not a governance system, but rather an approach to cultivating habits of mind, the relevant skillset, and the boardroom culture that allows for deeper reflection, critical thinking, and learning for issues or problems that demand it. Generative conversations can absolutely occur on topics that the board has delegated to the general manager for decision and action; indeed, in an ideal world, the general manager would be able to look to the board as a source of thoughtful discussion that helps to inform decision-making. ²

Getting started

At the outset, it’s important to bear in mind some of the general cautions noted by Chait et al. for boards considering a multimodal approach:

• All three modes are equally important to good governance, and each one merits time and care.

• Not every issue or problem is appropriate for each mode; don’t look to do generative work when an issue is obviously fiduciary in nature. Indicators that generative work is appropriate include ambiguity, such as when divergent interpretations or perspectives are at play; saliency, because an issue means a great deal to many; strife, because the potential for confusion and conflict is great; high stakes, because core values are involved; and irreversibility, because a decision or action would be hard to revise, whether for psychological or financial reasons.

• Do not allow generative work to become a tool to advance hidden agendas, to engage in back-door micromanagement, or to degenerate into “rabbit holism.”

• Don’t force generative work when the rest of the board or the CEO or general manager is reluctant, or where there is not a shared belief that the current governance is lacking.

• Embrace incrementalism, looking for small ways to build the board’s ability to govern in all three modes with intention and awareness.

A great place to learn about implementing multimodal governance is The Practitioner’s Guide to Governance as Leadership (2013), by Cathy Trower. Building on the work of Chait et al., Trower comprehensively connects their theory to practice and offers many tips and real-life examples from her work with boards that have embraced the approach of governance as leadership.

Breaking out of the status quo does not happen without commitment, diligent effort, and a little bit of courage. The potential reward is well worth the effort—namely, an engaged and thoughtful board of directors, with a deep understanding of purpose and the confidence and dexterity to govern wisely, well, and a la mode. •

¹ Specifically, a board’s work in the fiduciary mode is an expression of accountable empowerment, while the strategic and generative modes take place under the broad umbrella of strategic leadership as defined by the Four Pillars model. And, as noted below, generative work requires robust teaming. See “Four Pillars of Cooperative Governance,” by Marilyn Scholl & Art Sherwood, CG170 (Jan.–Feb. 2014).

² This kind of generative discussion is an example of a “safe strategic conversation” as described by Art Sherwood in “Cooperative Strategic Leadership,” CG147 (Nov.–Dec. 2011).

CITATIONS

Chait, Richard, William Ryan, and Barbara Taylor. Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons, 2005.

Trower, Cathy A. The Practitioner’s Guide to Governance as Leadership: Building High Performing Nonprofit Boards. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013.

Sidebars

Questions in Each Mode

Consider some questions that might arise in each mode for a natural foods co-op that is considering adding conventional products to its mix:

Fiduciary: What are the costs and other resources needed? How does it align with our existing policies? What are the impacts of adding another major distributor?

Strategic: How will it affect our strategic position? How will our stakeholders respond (members, employees, non-shoppers)? How will we communicate the changes and respond to any concerns?

Generative: How does this align with our core values, and where does it conflict? How do we reconcile any conflicts? How do we understand our fundamental purpose, and who are we truly here to serve? What questions and perspectives to we still need to ask and hear?

Techniques for Building Generative Practice

Silent starts: Before a major discussion, give each director two minutes to anonymously jot down the most important question relevant to the issue at hand. Collect and distribute randomly, then ask the group to read them aloud, and collectively identify the most crucial.

One-minute memos: At the end of a major discussion, give each member a few minutes to write down any thoughts or questions that they have not expressed.

Counter points: Randomly assign two or three directors and/or management to make the powerful counter arguments to a recommendation under discussion.

Role play: Ask directors to assume the perspective of stakeholders likely to be affected by the issue under consideration, and ask them to identify how those groups would frame the issue.

Breakouts: To counter groupthink, break into small groups during a meeting to consider key questions: Do we have the right questions? What values are at stake? Whose perspective is missing from this conversation? How else could we frame this issue? As a whole group, compare and discuss the questions generated.