Leaders in Democracy

If we created opportunities in meaningful participation by seeking win-win, it would be a game changer—in our relationships, in our customer service, in our strategies, in our partnerships, and in our innovative approaches to solving pressing social problems.

Democracy is hard. And because it is hard, it takes skills and practice and a willingness to work with others. Why do we do it? For me, it is because I deeply believe in what a healthy democracy provides—namely, opportunities for people to meaningfully participate in the process of reflection and change in our cooperatives.

However, I have to be honest, my faith has been shaken (but not broken) when I have observed fellow cooperators creating barriers to meaningful participation and dealing with their conflicting views in ways that hurt individuals, damage relationships, and destroy economic value that has been cultivated for decades.

Thus, this article is a call to action: a call to all cooperators to embrace the challenge of building our healthy democracies and to dedicate ourselves to learning the skills and investing in practice. Here, I focus on the critical area of conflict and how we address it through assertive cooperation.

Conflict: a choice of approaches

Conflict is natural. Conflict happens every day in ways both big and small. People (including cooperators) disagree on all sorts of stuff! As we learned from the team-development process, there will always be a “storm.i” The key to whether conflict turns into a destructive tornado or a nourishing summer rain is how we approach it and deal with it .

Conflict involves “parties who perceive incompatible goals, scarce resources, and interference from others in achieving their goals.ii” This definition contains key elements present in all conflicts, including interdependence (behavior of one affects the other), difference, opposition, expression, and emotion.

Unfortunately, we are saturated in an environment that takes an adversarial view as the predominant approach to dealing with conflict. This basically means, for me to win, you must lose. This is reflected in the daunting investment we put into protecting ourselves against litigation, the approaches that we most often see streaming to us on our devices, and sadly, the approach we often see within our co-op membership, our boardrooms, and our staff communities.

But isn’t this just the way things are? Don’t we just sometimes find ourselves in a situation where we simply can’t agree?

Well, yes.

Yet, if we allow ourselves to think more broadly, there are additional options. And these options are ones we can reach for first and regularly, rather than automatically going into a fists-up mode.

Think win-win. I first learned about this idea way back when reading Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective Peopleiii. He argues that people who are effective, make it a habit to do the hard work of finding solutions where both parties are able to win. He also argues this is beyond and better than compromise and certainly better than a habit of win-lose as the usual approach.

What if co-operators thought win-win? What if we embraced it as the preferred approach, learned the skills needed, and then practiced it until we were amazingly good at it? What if we created opportunities in meaningful participation by seeking win-win? It would be a game changer—in our relationships, in our customer service, in our strategies, in our partnerships, and in our innovative approaches to solving pressing social problems.

What will it take?

Requirement 1: Building a culture of assertive cooperation

A useful way to think about culture is “the way we do things around here.” Thus, the requirement is one where the way you do things includes being willing to assertively cooperate and then practicing it. And it is a must that leadership demonstrates this example over and over and over. Our member, board, management, and staff leaders have daily opportunities to lead by example, and to get there we must prioritize and consciously work to build this culture.

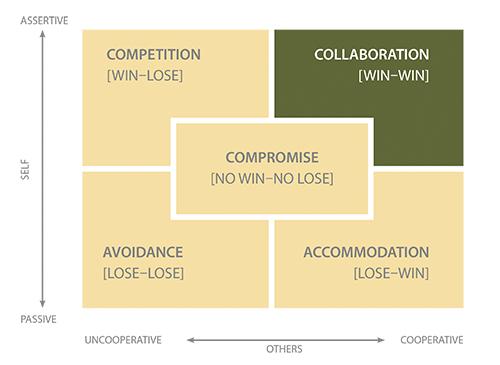

As you can see in Figure 1, there are various combinations of winning and losing situations, with the one in the upper right where everyone wins: a pretty good place to be! This is the assertive cooperation quadrant—here labeled “collaboration.”

The desire and the willingness to try to go there and to make it part of the way things are done is the first requirement for getting to assertive cooperation. Yet this is often difficult for people to do without backup: what if it does not work? This is covered below in Requirement #3.

A final piece worth highlighting is a culture that assumes positive intent. This is critical. If our perceptions start from a place that believes the “other” does not have positive intent, this will poison the culture, the practices, and the situation—which perpetuates adversarial cultures. This is not to imply one should be naïve, rather, it is starting in a place of assuming positive intent and then letting observations of behavior modify that position. For example, if a board member assumes another board member’s intent is to do harm, the entire interaction is set up for adversarial conflict and can only end up in one or both of the parties losing. Assertive cooperative never even gets a chance.

Requirement #2: Investing in the practice of assertive cooperation

In order to be able to realize assertive cooperation, cooperators will need to build talent around know-how and skills to make this happen, and then to keep learning until the practices becomes the norm. If it were natural to us, we would not need this article! And everyone would be winning a whole lot more often. Since it is not our natural state to be born with collaborative knowledge and skills, we need to invest in them.

There are many pieces of knowledge and skills that can be built. Here, I will cover a few key ones.

Principled Negotiation v. This is a fancy way of saying, “Figure out the why behind the what.” Folks take positions on how to do things or how things should be—this is the what. Behind that, people have reasons for taking these positions—this is the why. In order to get to a win-win place, it is important to be able to “abstract up” and share the why and then look for a mutually agreeable, and often better, what. This sounds easy—and reality shows that it can be very hard, especially if the culture and practice has been that of arguing and fighting over positions and the resources needed to take those positions.

XYZ formula vi. This is also known as an “I statement.” Oftentimes things can get tense when people behave in certain ways that can either be the root of the conflict or an accelerator of the conflict. Being able to keep the focus on the behavior of the other party rather than the person is critical. Why? Because behavior is flexible, while personality is relatively stable. We can choose how we behave. It is easier to keep the focus on behavior if someone says, “When you behave like X, I feel Y, and that is a problem for me because Z.” There are many variations of this formula. The point is for people involved to focus on what can be changed, own their reaction to it, and communicate clearly. Even if it is hard. Even when it is tempting to just rip into the person for being stubborn, mean, power-hungry, and just plain dumb (these accusations are unlikely to help a conflict situation).

To make assertive cooperative become our norms, we need to identify the opportunities to build our knowledge and skills and then be willing to invest the time and money into making it happen. If we do not, we know we will pay with time and money in dealing with adversarial conflicts that will arise and have been prevalent in our co-op communities.

Requirement #3: Reduction through empathy and systems design

Empathy building: To make any of the practices of win-win work, we need to actively build empathy for those who are not like-minded. Our co-op community often talks of the desire to be with like-minded people. The irony there is that if we want to grow our impact, we need to include those who have not been included. We need to provide broader opportunities for diverse people to participate in meaningful ways. Unless we are going to live on a homogenous island, we need to be embracing diverse views, and for that we need to build empathy.

Empathy is about understanding. Empathy requires listening and observation. Empathy requires one to leave one’s position and seek to understand the other. It does not ultimately require one to align or agree—rather, it is about understanding. And through this understanding, we set ourselves up to be able to seek out the “why” and to find the win for all. Opportunities to build empathy happen in each interaction we have with other humans. It also can be an intentional set of actions to seek understanding.

Empathy can reduce the intensity and quantity of conflict. People who understand one another tend to have less fear of one another and fewer preconceived notions. Having empathetic insight into others helps one gain foresight regarding where unhelpful conflict might arise, and this links to system design.

Designing for meaningful participation underscores that our systems matter. I’ve found that many co-op conflicts arise when opportunities for meaningful participation break down. And if this happens systematically over long periods of time, trust erodes, empowerment flags, and anger and frustration rise. Therefore, it is worth designing for meaningful participation. How might you design your systems in ways where people are able to meaningfully participate—where they can identify their disagreements and practice assertive co-operation?

We also need to take care that we don’t allow our systems to become so rigid that they keep us from achieving what we intend. The system is meant to support our efforts. This can be particularly problematic when we choose to rigidly hold on to the system when it is not working well and/or when we mistakenly apply a system that was meant for one thing to another where it does not fit. For example, policy governance is a good system for accountable empowerment that when mistakenly applied can create unnecessary barriers for communication and meaningful participation in our democracies.

If you create the systems, then it is your responsibility to change them if they are not serving well. This can range from customer feedback to strategic process. And this all might be harder work, yet we also know it is better.

Requirement #4: Back up plans

BATNA is a well-known acronym in negotiation: Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. Even when we build an assertive cooperative culture that seeks win-win as a standard, has the talent needed, and is abounding with empathy and great systems design, we find that sometimes win-win is not going to work.

Knowing this, we can build systems as backups. This may include a range of procedures, from grievances to customer complaint systems to decision-making. Sometimes even the best efforts at win-win may need to cascade to compromise or win-lose. The key is to make this the exception, rather than the rule.

Final thoughts: I am convinced that my fellow cooperators want to be leaders in how to build healthy democracies. I have seen great examples of people doing amazing collaborative work on very difficult problems. I also have seen us fall on our faces in spectacular and painful failures on what seem like straightforward issues.

We are often now asking ourselves, what is it that differentiates us from other organizations that sell local and organic foods? Our answer often is, “We are cooperatives!” The promise that this brings can come true and also become widely held if we truly embrace the challenge of becoming leaders in building healthy, democratic organizations. How we address conflict is central to our success. ♦

REFERENCES

i http://library.cdsconsulting.coop/building-a-positive-board-performance-....

ii Wilmot and Hocker, Interpersonal Conflict, 8th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

iii You may find it of interest that Covey did not ‘invent’ this concept. Rather, it is most often attributed to a student of Kurt Lewin, Morton Deutsch, who was a pioneer in game theory.

iv Original research: Thomas, K.W., and R. Kilmann. “Developing a Forced-Choice Measure for Conflict Handling Behavior: The MODE Instrument.” Educational and Psychological Measurement, 37, 1977: pp. 390-395.

v This is from Fisher and Ury, who were part of the Harvard Negotiation Project. They wrote the book, Getting to Yes: Negotiating an Agreement without Giving In—an easy, valuable read.

vi This formula is well known in various forms and was originated by John Gottman as “I statements.”