Walmart vs. Food Co-ops

If you walk into any of the 4,132 Walmarts in America that sell groceries, you will find only 11 percent of its produce was grown in the same state where it’s sold. That’s Walmart’s definition of “local produce.”

Six years ago this month Walmart announced a formal commitment to put more locally grown food in their U.S. stores. The retailer promised to double its local produce sales from 4 percent to 9 percent by 2015. The company claimed in 2012 to have topped that goal at 11 percent locally sourced produce sales. To flip that: 89 percent of the food Walmart sells is not local.

In testimony before the U.S. Senate Agriculture Committee in 2012, Ron McCormick, Walmart’s Senior Director of Local Sourcing, said: “Today, consumers all across the country—-not just those who shop in our stores—have a growing interest in where their fruits and vegetables are grown. Our own consumer insights research shows that more than 40% of our customers tell us that buying local produce matters to them.” McCormick quoted a Food Marketing Institute survey which found that consumers “like locally sourced produce because it offers more freshness, and they like supporting local economies.”

But a 2013 report produced for 9 NPR stations found there was “little evidence of small farmers benefiting” from Walmart’s local sourcing. One organic farmer in Missouri told NPR he didn’t know anyone who has sold successfully to Walmart. “They tend to try to force people into lower prices than feasible,” he said. According to NPR, of the eight farms highlighted on Walmart’s locally grown website, five were very large farms, with annual sales in the millions of dollars.

The USDA’s Economic Research Service reported in 2013 that the 20 largest food retailers — led by Wal-Mart — accounted for 64 percent of grocery store sales in America, up from 40 percent in 1993. “One contributing factor...has been the steady growth of Wal-Mart supercenters.”

“The more dominant Wal-Mart becomes,” author Stacy Mitchell wrote in 2011, “the fewer opportunities there will be for farmers markets, food co-ops, neighborhood grocery stores, and a host of other enterprises that are beginning to fashion a better food system — one organized not to enrich corporate middlemen, but to the benefit of producers and eaters.”

Walmart’s sense of “local” is one-dimensional. “It’s not just geography; it’s scale and ownership and how you treat your workers. Walmart is doing industrial local,” explains Andy Fisher, former executive director of the Community Food Security Coalition.

But there is another definition of “local” in America, one that is not found in the cavernous superstores. If you walk into any of the estimated 330 food co-ops in America, you will see an emphasis on “locally grown” products. Almost half of these grassroots businesses are members of the National Co+op Grocers (NCG), a cooperative for retail food co-ops located in 38 states, with combined annual sales of nearly $2 billion, and over 1.3 million consumer-owners.

“Co-ops’ current focus is on regional agriculture,” says filmmaker Steve Alves, who has just released nationally a film entitled Food For Change, which was underwritten by 126 food co-ops in 36 states. “They are part of the loose alliance of what is called the ‘local food movement.’”

Alves’ provocative new documentary film looks at the resurgence of food co-operatives in America, and how these grassroots groups are creating a quiet revolution in food quality and distribution. “The goal is to take back our food chain from the corporate chains,” Alves says. Food For Change is being screened in 43 locations in 22 states as part of October National Co-Op month.

“Corporations control what food reaches our table,” Alves says. “But locally-controlled food cooperatives are filling their shelves with fresh, local produce, giving all of us a new vision for feeding our families. This is how we turn food into change.”

Alves describes his film as “one part food, two parts politics, and three parts economics.” Food For Change traces the co-op movement’s quest for whole and organic foods, and its goal of sustainable food systems. The film profiles several food co-ops that have revived the economics of entire communities—-right in the shadow of corporate agribusiness and national supermarket chains.

Consumer-led food co-ops have played a key role in the debate over profit-driven capitalism vs. locally-controlled economic enterprises. Born in the heartland, cooperatives were seen as the middle path between Wall Street and Socialism. “Food Co-ops were a byproduct of the Great Depression,” says historian David Thompson, who is featured in Food For Change. “The disparity in wealth between the haves and the don’t haves was the spark that ignited co-ops. As co-ops grew, they restored hope to millions of Americans who began to gain some economic control over their lives.”

“Today we’re experiencing a renaissance of American food co-ops,” adds Sean Doyle, General Manager of Seward Co-op in Minneapolis, who also is featured in the film. “These are not marginal enterprises—they are flush with capital, and making a difference on Main Street, U.S.A. People are once again taking more control over the economic forces in their lives.”

Walmart told the Senate Agricultural Committee in 2012 that buying locally “allows us to strengthen ties with local communities...Sourcing from local farmers is one more way that we can live our commitment to our communities.”

But at the grassroots level, the local food co-p is where the real commitment to community lives. This growing local movement represents our best chance to break the chains that restrict who grows our food, the quality of the produce that reaches our table, and the democratization of our food distribution system.

View a trailer for Food For Change.

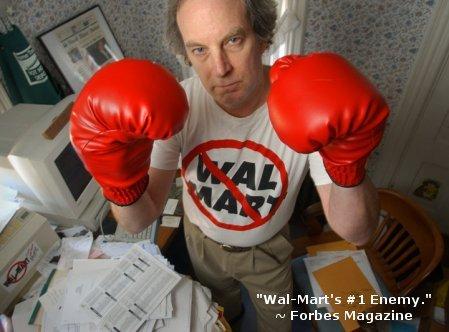

Al Norman is the founder of Sprawl-Busters. His most recent book is Occupy Wal-Mart.