Staying Healthy in an Unhealthy Economy

Well, the other shoe has dropped, and it’s making the headlines something we are experiencing, not just reading. When the initial signs of the sagging economy came to light, it was fairly abstract for many of us—billions of dollars in investments being lost and large companies either going bankrupt or being gobbled up by even bigger companies. But our industry was not experiencing a corresponding impact. There was even talk about people staying home and not eating out as a potential boon to the grocery industry. Now the loss of jobs is growing steadily, many people’s net worth has been reduced by a staggering percentage, and many of our neighbors have lost or are losing their homes.

Unfortunately, this financial mess is deep, and we can expect additional bad news in the near future. Economists predict national unemployment of 10 percent or more during the next two years. We, in an industry that serves a mix of people who see our products as either necessities or extravagances, need to consider what to do to keep our cooperatives healthy in a deteriorating economy.

Sales declines and planning changes

Anecdotal data shows a significant decline in sales for our cooperatives. I have been in the industry since the 1970s, and until now I have never seen declining sales related to anything but a poorly run operation or significant new competition. The Wall Street Journal reports, “Consumers are cutting back on food spending, eating out less and choosing generic products over brand names. In the fourth quarter of 2008, consumer spending on food fell at an inflation-adjusted rate of 3.7 percent, the steepest drop since the government started keeping track 62 years ago.”

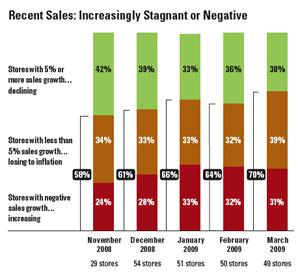

CoopMetrics started gathering monthly co-op sales data in November 2008 to produce more timely information. Looking over the data, what does it show when compared to the previous year? (see chart)

November: 29 respondents, 24 percent lost sales and 34 percent experienced less than

5 percent sales growth.

December: 54 respondents, 28 percent lost sales and 33 percent experienced less than

5 percent sales growth.

January: 51 respondents, 33 percent lost sales and 33 percent experienced less than 5 percent sales growth.

February: 50 respondents, 32 percent lost sales and 32 percent experienced less than 5 percent sales growth.

March: 49 respondents, 31 percent lost sales and 39 percent experienced less than 5 percent sales growth.

Considering how inflation impacts our sales picture, we can assume that co-ops reporting under 5 percent growth may actually be losing ground. If so, more than 60 percent of the reporting co-ops are losing sales compared to the previous year.

What are we doing about this in our stores? I contacted a number of general managers and operations managers and asked what they were doing or planning to do to maintain financially healthy organizations. Through their responses. I learned of approaches to deal with declining sales, lost shoppers, margin management, inventory control, marketing, expense reduction and employee morale.

One tactic mentioned by more than one manager is a change in their planning processes. Planning, in this fast-changing environment, needs to happen more often and with shorter cycles than before to be effective. Terry Appleby of Hanover says, “We are shortening planning cycles, with each department doing very simple business plans a quarter at a time. Departments are looking at sales trends, gleaning whatever information they can get from movement reports, and strategizing about member needs in a down economy.”

Marketing

How are declining sales being addressed? The tactics shared include enhanced marketing focus, but not necessarily more marketing dollars, with a greater emphasis on the in-store message and merchandising. Some broad approaches and some very specific ones are offered.

Clem Nilan, general manager of City Market in Vermont, cautions, “I think one of the biggest mistakes that people make when faced with a recession is to cut marketing. We’ve hired a media broker, and in conjunction, we invested in a professional survey of our customers. What our media broker was able to do was take our budget and spread it across the calendar, specifically targeting our core customers (while also being effective with all of our shoppers).

“Another marketing initiative was to take a hard look at how we do ‘four-walls’ (in-store) marketing. We came up with several teams who, with fresh eyes, surveyed our store. We were looking to see how we marketed our store in three ways: the first was standard POS signage, the second way was governance (meaning co-op values), and the third was all product-related signs such as fair trade and product attributes. The findings showed us that we had lots of opportunity to put our message across more effectively within our store.” Clem and his team are using both professional assistance and staff expertise to implement new tactics to present City Market to its community.

Kenna Eaton from Moscow Food Co-op in Idaho agrees that now is not the time to cut back. She says, “I added an outreach position in the fall. I think it’s especially important right now to be more visible, not less—more in-store promotions (like tasting events), more outreach (wellness fairs, etc.), more fun events (for example, a movie series about food followed by a potluck and discussion).”

Art Ames of Berkshire Co-op in Massachusetts has a slightly different approach. “Essentially, our marketing shifted from some advertising to education and participation. I’m on the Chamber of Commerce now, my marketing team goes to a variety of local events and joins committees, and we write to the local paper on issues and show up on local radio. In other words, we take advantage of ‘free’ publicity.”

At The Grain Train in Michigan, General Manager Carrie Livingston has taken on a very inexpensive new approach: weekly emails. “This keeps both member-owners and shoppers who opt in to keep in touch with the store. We include everything—a great buy that week, when the next Member Appreciation Day is, current and next month sale flyer (so shoppers can plan ahead), current events at the store, a link to newsletter online.” Like Art’s approach, Carrie says they are getting more involved locally. “We are Petoskey’s downtown grocery market. We previously were overlooked—even by people who worked within a few blocks. Getting the store involved with the community through sponsorships, donations and good old word of mouth has changed the community’s perception of us. We now have a presence at downtown events and Chamber of Commerce networking and a face that people can associate with the store, which makes the store not seem so ‘foreign’ to people not used to shopping in the natural foods sector.”

The approach of Chris McElwee from Tidal Creek in North Carolina is focused on being cost-effective: “We are working on ways to get free PR. Examples: wine tasting and chocolate on Valentine’s Day, and a food drive for our local Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard. We are bringing in school groups with teachers and parents and doing store tours—talking a lot about allergies and alternatives—this has been a huge success and brought in new customers.”

Michelle Schry, general manager of People’s Food Co-op in La Crosse, Wis., says, “We’ve made an intentional shift away from ‘long-term brand building—feel good marketing’ to strategies that are specifically focused on driving sales in the store. Our messages will be much more focused on product, value and choosing to support the local economy during tough times.”

We see a number of marketing approaches in these examples, and many of them are inexpensive (weekly emails, store tours, participating in a merchants’ organization). One consideration is that a “random” approach is unfocused and is likely to be financially less effective. I suggest that while we need to act fast, we also need to act smart. I normally coach those I work with to plan out an annual marketing calendar and budget. But, in this environment, I suggest quarterly plans that are reviewed monthly, with a budget and a process for evaluating each area of investment in each quarter. This may mean using coupons to be able to track effectiveness of the advertising venue. These reviews will help you understand where it will be beneficial to put energy during the next cycle.

Merchandising

As we see shopping patterns change, we need to adjust our merchandising to maximize our ability to capture sales. Kenna of Moscow Food Co-op says, “We’re seeing a shift in shopping habits, but we’re not yet far enough along in this year to say exactly in what way—so far, fewer transactions, higher average basket. Lots of cherry-picking the deals, lots of coupon redemption, increased case sales [and their discounts]. So we’re playing into that, ensuring our deals are well signed and that we have plenty of products on hand.”

Art is addressing buying pattern changes through Berkshire’s merchandising approach. He explains, “We are constantly analyzing monthly movement and SPINS data. We’ve changed out almost 20 percent of our frozen product mix, are more aggressive with sampling, and tie in higher margin product on displays, as we also continue to focus on sale merchandise.”

John Eicholz of Green Fields Market in Massachusetts says, “We are reinvigorating category management, specifically to replace high-cost/premium items with faster moving, more economical ones where that looks good.” I have read that consumers are moving more towards store brands and away from name brands as one means of managing their food budgets. Greenfield’s approach offers lower priced items to maintain category sales.

Michelle of People’s Food Co-op says, “We did bring in a ‘private label’ line of products from our conventional grocery distribution co-op (Certco). The line is called Full Circle, and we currently carry 148 SKUs. We’ve carried a few of these products for the past 18 months, but in July 2008 we saw the writing on the wall with where the economy was headed, and we very intentionally focused on bringing in SKUs in every major center store category to provide a lower cost alternative. The Full Circle line includes both organic as well as ‘clean’ natural products. The price points are anywhere between 10 percent and 55 percent less than the comparable national brand, with the average being 30–40 percent less. We haven’t seen these products act as ‘category killers,’ but we’ve continued to see customer counts increase, even as average baskets have declined somewhat. Many folks are trading down on items that they see as ‘staples’ versus their product favorites. Best sellers among our private label include organic extra-virgin olive oil, which comes in at 50 percent less than the comparable national brand, organic maple syrup, organic peanut butter, and organic tomato-basil pasta sauce. These are some of the private label items that have made it into our top 100 best sellers. Sampling seems to be crucial in getting this private label off the ground. Once people try it, they’ll buy it.”

Michelle adds, “Reducing SKUs, improving allocations and improving overall store turns are big areas of focus for us right now. Inventory management in food service areas has also gathered new importance—improving turns and making better use of our delivery schedule are just as important there as they are in center store.” Improving turns in our stores leads to freeing up cash, and Michelle is appropriately focused on this approach.

Clem of City Market has been working to maintain a strong price point on the number-one product in the number-one traffic-producing department. He says, “The number-one selling product in the store is bananas. We’ve seen the cost of bananas climb to the point where we’ve had to raise the margin on all other produce products by 1 percent in order to maintain a retail of $.99. We recently crafted a deal with our local produce company to have no banana returns (except for those happening on the day of delivery) in order to get a concession on pricing from them. We think banana pricing is probably the most well-known of any price point that there is, and we are struggling mightily to maintain it while not losing department margin.”

Jim Dobis, operations manager at First Alternative in Oregon, says what I hear often: “I will be analyzing submargins, turns, movement and using SPINS, etc., to determine drops in particular. Most of the department managers like to add stuff, just not do the drops.” It is always important to review product movement reports regularly and get rid of your slow-moving products (assuming they aren’t must-have items). This process should be formalized so all product managers have a schedule in which to accomplish this (I suggest quarterly). Living with poorly performing products is a luxury we can no longer afford.

In my work with co-op stores, I see so much opportunity to improve merchandising approaches, from easy to more difficult changes. One tactic implemented by too few stores is the daily walk through—an individual or team walks the store by 10 a.m. and makes note of issues such as cleanliness, signage problems, and out of stocks, and directs these issues to those who need to fix them. This approach can create a more consistent presentation to our shoppers. Many of our stores can improve their signage or shelf set spacing, tighten product introduction and discontinuation approaches, and review each category’s profitability/space allocation. One tactic that has always worked, even though it is counterintuitive: reducing the number of SKUs per category.

No matter what you feel about your current operation, it’s imperative to take a fresh look at your store and make necessary changes quickly. Let’s remember that retail is, in large part, constant experimentation—if you aren’t trying new approaches, you may be falling behind.

Margin management

Anyone who has attended one of my margin management trainings knows that while I spend a lot of energy working with managers on controlling their margins, I always explain that margins are just the tools, not the end game. The end game is gross profit, so at times we may need to give up margin to accomplish our gross profit goals.

Paul Cultrera of Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op says, “We’ve been doing some extensive price surveys with the local competitors, and after we analyze the data we plan to make some changes in our margin targets (some up, some down) to bring us in line.”

As with the example of City Market’s bananas, sometimes you need to look to other products to gain margin dollars as you reduce the margin dollars you bring in from typically highly visible and competitive products that do not meet the store’s margin goals. This is one of City Market’s challenges, says Clem. “There’s another aspect to margin management that is trickier: when our customers downgrade to lower margin products. For example, here at City Market, about 75 percent of our products are natural and 25 percent conventional, and conventional products have a lower margin than the natural. With this significant shift into the conventional products, we can lose margin. We haven’t, though, mostly by adjusting margin on natural products.”

Terry described Hanover’s approach to margin at this time as “primarily making more use of category management to pinpoint areas of increased movement to determine the shift in product mix. We have reduced the number of SKUs on sale and are taking the margin on sales items and not putting them on special.”

Chris said Tidal Creek has instituted the practice of “doing cyclic price audits in all departments.” This will help maintain the integrity of their pricing approach and reduce lost margin dollars from cost changes that are not caught when they happen.

At Co-opportunity in Santa Monica, Bruce Palma has directed the deli (a department that had approximately $2.8 million in sales last year, with a majority of products coming from vendors) to produce more products in-house as a way to enhance margins without necessarily raising prices. They have also taken on a value-added approach in their produce department by “offering cut fruit and veggies at much higher margins.”

Margin management has a number of tools that can assist you, but the one I feel can be most effective is contribution margin spreadsheets for each category. This tool will allow you to manipulate margins on paper, prior to putting them into operations, to forecast potential results of your margin approach. Finally, remember that the least negative impact you can have on your customers while increasing your margin is to manage your shrink effectively.

Labor management

All else can seem easy compared to managing labor, especially when we have stagnant or declining sales. While most aspects of retail management focus on the numbers and may seem distant from people, managing labor directly impacts people daily. Everyone I spoke with talked about the need to ensure that our co-op value of fair treatment of employees is in front of us as we manage labor. Most co-ops were looking to attrition and not filling vacant hours as a primary tactic to reduce labor and ensure that those who want to work have a job. But is this a tactic that can stand alone?

“Hanover’s sales have been in a downward path since November, and as of late February are entering negative territory,” says Terry. “Our goal is to weather the crisis and not lay off staff, by shrinking FTEs through attrition. We have become more concerned about lack of productivity in some staff and are taking quicker action when things are not working to the co-op’s benefit (i.e., terminating employment). We are not hiring when people are terminated, find new jobs, or retire. In the past two weeks, we have eliminated six FTEs. We cannot always control the departments people leave, so in areas where there is higher turnover (prepared foods and deli, for example) we are moving staff from other areas. Thus far, staff have been accepting of this strategy and are grateful to have jobs.”

City Market analyzes labor every week since it has weekly payrolls. Says Clem, “It’s a pretty straightforward process to scale down labor to sales in all of the operations departments. Being a college town, we have historically had a high labor turnover, although the recession has dramatically slowed it. Turnover is sufficient to allow us to use attrition to maintain operational labor at the right level. We consider operational labor to be a variable expense linked at the hip to sales. What’s a little bit trickier is administrative labor. Admin is more a fixed expense than a variable, in that turnover is extremely small. In a worst case scenario, I would probably approach scaling back hours rather than layoffs.”

At Berkshire, Art “announced that we had imposed a hiring freeze and we would trim payroll and increase efficiencies. We also told staff that if we all worked together that there would not be any layoffs or forced reduction in work hours. We also told them that poor performers would no longer be able to slip through the cracks. Since then, payroll percent has declined, and we are using fewer weekly payroll hours, some people no longer work at the co-op, and morale is high. There is a sense that we are all in this together, and by facing the situation right away, we eliminated the fear of not knowing what to expect.”

Jim reports First Alternative’s approaches. “We use paid subs for extra labor and emergency hours, so all the departments have some hours to cut without affecting their regular staff. We are left with a situation in which regular line staff can get back up to 40 hours, but maybe they have to work six days to do so. We are analyzing our sales by the week and comparing it to our labor numbers to get a jump on any needs for department cuts. If a department goes over in labor, we not only expect a cut to get back to budget relative to sales, but they need to make up the hours they are over budget within two pay periods (we pay every two weeks). Lastly, we have made cuts to management. At the beginning of each year, we give an across-the-board inflation pay raise. This year we only gave the 2 percent increase to line staff, not management. And beginning March 1, to meet our admin budget we are cutting all management 5 percent (both admin and operations). Out of the 30 or so managers, most understood and accepted the 5 percent cut. It’s much easier to look staff in the face and cut their hours if you have had cuts, too.”

First Alternative took another specific action because sales were below budget and were expected to be so for the foreseeable future. “We adjusted our benefits package and saved some labor dollars there. We had been paying for meal breaks for working at least a six-hour shift, and we give a 30-minute paid meal break: gone as of Feb. 1. This saved us an amazing amount in labor dollars. We had departments cut back their hours in January to match what they were using in September, our last good labor-to-sales month of 2008.”

Paul says that at Sacramento, “We are not replacing anyone who leaves, though turnover is very minimal. Where labor cuts in a department seem necessary, we are offering workers hours that may be available in other departments: sales growth in grocery, wine/beer/cheese, and deli remains positive, while sales growth in meat, wellness, and produce is slipping.”

Breaking from the others, Green Fields is “raising our entry wage by $1.07 (really) and adjusting the rest of the scale upward,” says John. “This may be crazy, but that is what the livable wage went to, and we are sticking with our commitment to it. We have asked staff to help us improve productivity to cover the cost. We are also scheduling leaner, leaving spots empty if we can, and being sure everyone has a list of side work if they are idle.”

At Hanover and Berkshire, they are looking at productivity in their efforts to manage their labor. At Sacramento, Paul uses sales per labor hour in scheduling department hours. Being more labor-efficient is an area where we can improve as an industry. Using CoCoGap, you can see how the top quartile is performing. Ask yourself, “Are we in the top quartile of stores, and if not, why?”

Establishing specific department productivity goals is the first step in focusing your store on improving. Tools such as CoCoFiSt, CoCoGap, flow charts, sales-per-labor-hour scheduler and pieces per hour (stocking standards) can be used in this effort. Flow charting as a team and discussing ways to streamline processes can be very powerful and connect staff to improving efficiencies in their daily tasks.

Inventory

For most of our stores, if we don’t own the building, inventory is one of our two biggest assets (equipment being the other). Inventory is the asset that needs the most managing. Since inventory can turn to cash more quickly than most noncash assets, it is essential that we run tight inventory to keep as much cash as possible available for other needs. Using inventory turns as a measure of your efficiency is key to improving inventory management.

At Tidal Creek, Chris has “requested all product department managers reduce backstock and use the distributor/manufacturer as back room.”

Hanover staff is now talking about analyzing inventory levels and turns as a direct result of Terry’s open book approach (see Communication, next column).

Setting specific department goals, backstock reduction, reviewing data, setting targets, purchasing budgets, using Scan Genius, setting par levels for products, denoting top sellers on the shelf tags—all are tools to run a more effective inventory level.

Other expenses

Other expenses is an area that is difficult to change because a number of these expenses are fixed (rent), or you have no bargaining power (utilities). Still, there are line items that can be modified: insurance, cleaning, linens. Remember that most service suppliers are also feeling the crunch of the deteriorating economy, and approaching them with the idea that we are in this fine mess together may open dialogue you never thought possible.

Tidal Creek has all office supply requests going through one person to monitor this line item more closely.

People’s is looking at all their line items and sharpening their pencils to keep expenses manageable. Michelle says “We’re renegotiating contracts for everything from linen service to credit card processing. We’re also looking at small changes in store temperature, packaging supplies, discounts at the register. All things are on the table right now—we may decide to leave some of them there, but everything is going to be picked at, and our decisions will be intentional.”

Communication

Berkshire’s approach to information for staff and the community is not unique but refreshing. As Art puts it, “As the situation changes, we’ll continue to educate our own staff, ask for their thoughts and explain our actions. It may take more changes in the coming years to survive and flourish, and it’s impossible to be successful if our employees are kept in the dark. We’ll also be honest with our owners and let them know what is happening, rather than what they may like to hear. I think as long as we keep our values in mind, and realize that most communities need a co-op now more than ever, this could be as defining a moment for co-ops generally as the 1970s were when we brought organic to our customers. I think we are going to choose to look at this new economy as an opportunity rather than as something to fear.”

Terry echoes this sentiment for Hanover. “We are sharing data with staff, and they are more aware of problems with labor and general expense control and sales declines. They are helping to come up with creative ideas on being more productive or otherwise improving operations.” The center store department (grocery) in the Hanover store had a “game” to reduce out-of-stocks over a two-month period. The department had 250 out of stocks at the beginning, got them down under 90 and is keeping them under 100.

“So far, my focus has been to raise awareness among management,” says John of Green Fields. “Since we all like to think positive thoughts, we have to be intentional about staying in alignment with reality at times like these. I have been bringing in outside data on retail sales, unemployment and employment, both nationally and in the Greenfield ‘Micropolitan’ area (that is a real term), also gross domestic product, inflation, and wage data. We also have looked at our sales graphs for the last several years, which make the recent sales drop off pretty easy to see.”

It’s daunting to review what these managers are doing, a combination of tried-and-true as well as new approaches to deal with the economics of the moment. There is no greater stress on an organization than laying off staff, and this is the approach of last resort for these managers. There are many other excellent ideas to consider in reducing the negative impact of slowing sales—from less-expensive marketing to line-item-expense reduction to enhanced focus on productivity to stronger inventory management and more frequent planning cycles.

In politics, they say that in tough times you can get greater legislation through, such as Roosevelt’s New Deal and Obama’s stimulus package. We co-ops can also do this—take this opportunity to strengthen implementing our values and running tighter operations. Yes, we should be doing this regularly, but today, what is the alternative?