The Death of the Supermarket?

In May I attended the 2016 HOW Design Live conference, an annual event that conceives of problem-solving as one of the primary jobs of designers. Julie Anixter, executive director of AIGA, the largest professional design organization in the world, reminded us that designers today are innovators, business strategists, visualizers, researchers, narrators, integrators, educators, and systems thinkers—among other leadership roles.

I like this, in part because it applies to people in our cooperative grocer industry, too. I think you can easily argue that cooperators today are also “all of the above.” Our work involves the creation and distribution of vital products and services, as well as the conception of solutions to common yet intractable problems: Food justice. A sustainable food system. Cooperation as a principle of governance and ownership. Community empowerment.

I was drawn to HOW Design Live in part because of two sessions organized by Debbie Millman, host of the influential podcast, “Design Matters.” The topic was (drum roll, please) “The Death of the Supermarket,” described as a lively cultural and anthropological discussion of changes in the way shoppers access consumer packaged goods (also known as CPG essentials).

Do the people on this panel know something we don’t know, obsessed as we are with rapid changes in our competitive grocery landscape?

I knew the ideas in that room would bump up against the theme of CCMA 2016, “Disrupting the Future: Cooperative Food and the Next Generation.” What could be more disruptive, after all, than supermarket “death”?

The panel examined the ways in which same-day delivery of essential consumer packaged goods is rendering supermarkets less necessary. In addition to big-box stores claiming turf on the edges of our cities, online shopping disrupts the future of food. What’s going on when people living in both rural and urban areas gather their “groceries” in a broad array of ways: from the garden, the farmers market, Walmart, the specialty shop, and the internet? How does a food co-op fit into the mix?

As co-op grocers, we do field work on these topics every day. We are inadvertent anthropologists of food. We hold conversations with our customers and discuss food access issues among ourselves.

More on disruption

Yes, we do hold conversations! Later, at the CCMA conference, I attended Brittany Baird’s session, “The Future of Food: A Cultural and Operational Blueprint for Surviving in a Changing Landscape.” Baird has recently joined CDS Consulting Co-op as an operations and management consultant; she also is the interim general manager at New Orleans Co-op in Louisiana.

The buzz in that room was intense, especially when we turned to one another to discuss the obstacles to change in our co-ops. As Brittany said, now is a critical time to have conversations about who we are, where we are going, and how we are going to get there.

Our common co-op theme has shifted from what Dave Olson at National Co-op Grocers identified last year as the “new normal” of increased competition to the challenge of courageous leadership. Increased competition has forced us to focus in very positive ways on becoming better grocers: improving pricing and promotion strategies; controlling labor costs while increasing wages; building core competencies to achieve more robust and engaging workplace cultures.

We have stellar examples of courageous leadership: Dan Arnett, chief cooperator at the newly merged Central and Tacoma co-ops in Seattle, mobilized the notion of solidarity to unite and dramatically improve those stores. Another instructive story: Sean Doyle, general manager of Seward Co-op (and one of two winners of this year’s Cooperative Service award), faced—and withstood—resistance on the road to the new Seward Friendship store.

From tacky to tactile

As growth in the natural products industry has accelerated, co-ops have been focused, for good reason, on product mix, promotion, and price perception. Processed foods such as non-GMO Campbell’s soup are getting a redesign. Conventional supermarkets are stripping back service where they can, or they are going the route of the department store with food aisles next to lawn chairs, swim fins, and animal toys.

Baird at CCMA emphasized the fact that co-ops are no longer the sole point of access for organic foods, nor are they buying clubs arranging for good deals on once hard-to-find natural products. As supermarkets have become larger and cheaper, integrating our consumer packaged goods essentials in with everything else under the sun (especially on the web), they’ve diluted one of our reasons for existence. The line is thinner and thinner between our stores and those we used to consider “indirect” competitors.

And yet the feeling in the room at the “Death of the Supermarket” was dismay at the “emptiness” of these huge stores filled to the rafters with packaged goods. One global future forecaster, Sem Devillart, described how the birth of the modern supermarket took place after World War II, associated in the U.S. with car culture (the freedom of the road), abundance, and the newfound convenience of canned goods and frozen foods.

Devillart argued that food stores in the future will move in another direction, reclaiming the “haptic” (or tactile) pleasures of the senses. “Supermarkets,” she argued, “will need to redesign themselves in relation to a more biological world view.” Consumers have learned to be suspicious of long-dead, processed foods, filled with purposefully killed nutrients. They are in search of pre- and probiotics, of local foods, and ingredients that have a marked impact on their health. There is a new appreciation for produce.

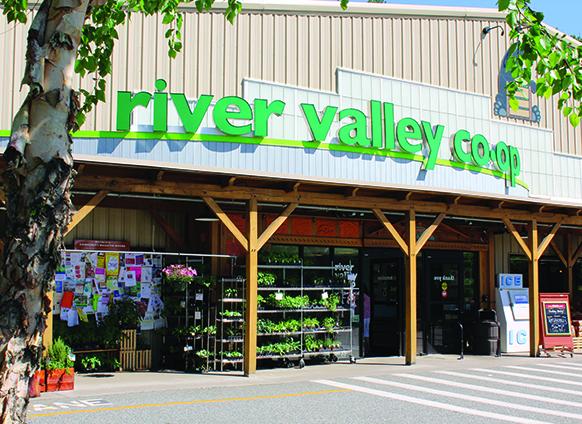

I thought of Devillart’s talk while on a CCMA tour to River Valley Co-op in Northampton, Mass. This store, under the leadership of General Manager Rochelle Prunty, has recently been remodeled. Located “between a rock and a highway,” the redesign includes high windows revealing a quarry wall and tall evergreens, flooding the back of the store with filtered light. Other elements, including an outside covered patio, make the store a magnet for community engagement. The produce section was gorgeous, filled with local items promoted as “Co-op Deals.”

People need to eat…and to socialize. Those needs aren’t about to go away, even as the range of ways we acquire food mutates and expands. Co-ops are designed with people in mind, giving their shoppers diverse tactile experiences, including the chance to connect with one another.

Connecting with one another is more necessary than ever, as we broadcast our co-op identity and aim to be THE excellent grocer in our town. As Baird and others at CCMA noted, the future is going to be disruptive—there is no doubt about that. “Co-opy cats” will come to town. The widespread embrace of natural foods (a good thing) puts new stresses on product procurement. It can be argued that, for all of our strengths, we lack a unifying co-op vision. That, too, is a challenge of courageous leadership.

Sticking to our principles will help us all ride out some of the current trends—the so-called “death of the supermarket” does not necessarily predict the demise of the co-op. The future is our to co-design.

Photos: River Valley Co-op—between a quarry and a highway

Exterior of River Valley Co-op