Cooperative Communication Conundrums

To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives... The future is an indefinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of that that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.—Howard Zinn

A rumor starts...employees aren’t being treated fairly at the co-op. Funds are being misused. The board is selling out—it wants to make the co-op “corporate.” Even when a cooperative is sending a strong message about its identity, being part of a community is to be part of a conversation about that identity, about the cooperative’s role, and, quite honestly, about all of the details of its organizational life. And that’s okay, to a point.

But I want to say something to you: you can lose your co-op. On the desk in front of me are two books. Laurel’s Kitchen, first published in 1976, promotes healthy, mindful eating and cooking in a community centered around the Berkeley Co-op. It is inspiring and beautiful. Beside it is a book edited by Michael Fullerton in 1992, What Happened to the Berkeley Co-op: A Collection of Opinions. I want to say it again, differently: your co-op could close its doors, and there could be nothing left except a collection of opinions about why.

The cooperative grocery stores that we take for granted are shaped by forces both around and within the cooperatives. A tremendous wave of competition threatens them from outside. People want healthy, clean food—and that’s good news. Yet it is a clarion call for us to distinguish ourselves in the market: what more do we offer?

At the same time, members are holding their co-ops to high standards at every level: socially, economically, and environmentally. This is also good news, but it can sometimes feel challenging, because we bring to our cooperation a wide range of priorities. The leadership challenge is to bring those often-competing priorities into balance: to stay connected to the economic reasons for our cooperation. We need to cultivate skills to hear, shape, and tell the story of how our cooperative functions as our agent in the marketplace in a world where social media has tremendously accelerated our ability to communicate.

We all have a sense that cooperation requires work. But it seems sometimes that hostility and anger that are particularly painful and acute can flare up within the membership of a cooperative. Why is it that trust seems to break down, why can it feel as if our closest community is composed of enemies, not friends? What skills can we cultivate to embrace controversy and in doing so strengthen our cooperatives?

This article explores these questions, without naming names, through the lens of some recent—but not too recent—internal cooperative controversies. “The names have been changed, to protect the innocent” (and some identifying details have been changed, too).

Case study: too corporate?

When a successful large co-op hired a general manager with experience in the conventional grocery industry, a group of members became concerned that their cooperative was veering away from cooperative principles and would become “too corporate.” Changes in the store staffing, a rebranding effort that changed the look of the store, and some changes in the product mix caused concern among a vocal group of members.

Social media quickly spread the conversation around the community. Was the board upholding the interests of members, or was it selling out? Tensions became high around the election of the board members. It was a hard time, and board elections two years in a row were highly contentious affairs. Nevertheless, three years later, many of those concerned members are helping with community projects supported by the co-op’s newly expanded store.

What helped? What didn’t help? Although board members felt stressed and beleaguered when the co-op was being criticized, they focused on fundamentals. They worked the systems they had in place. They worked toward alignment among themselves, with their members, and with their general manager.

It was a long process. There were volatile meetings where harsh words were spoken on both sides. The board focused on data and on strengthening its internal systems. Board members patiently and consistently listened and talked to members both inside and outside the board room. Two board members in particular went above and beyond during the most difficult times, supporting one another and their general manager with long phone calls and meetings.

When questions arose about board candidates, the election committee fell back on their existing policies and applied them consistently. Over two years, board members worked hard to strengthen their governance system, even recruiting back a former board chair to lead them through the stressful time. Most importantly, the board stuck to its vision of an expanded co-op and backed its general manager. The opening of the newly expanded store was a pivotal point, transforming the cooperative profoundly and bringing the vision of expanded cooperation to reality.

Case study: financial missteps?

At another cooperative with a strong business enterprise, simmering disagreements arose within the community about the wisest fiscal path. While the board and management had worked in alignment for many years, their work could be seen as having focused on the relatively immediate rather than long-term future. The timing of a key decision by the general manager about internal financial matters coincided with sudden board resignations just weeks before the co-op’s annual board election. A newly emerged board majority elected new leaders and fired the general manager, leading to tremendous insecurity among the co-op’s staff and members.

What worked? The new leadership maintained the board’s existing systems and procedures and conducted a successful board election that brought new board members into the dialogue. During the few but long weeks while the election was underway and while the new board was getting up to speed, well-defined existing board policies guided and shaped the board’s thinking and decision making. Board members listened to staff and to community members extensively and put in countless hours to understanding the conditions that had led to the upheaval. In the end, they made what seemed to many an innovative decision that made the community feel heard: they rehired the general manager. As a result, the co-op is thriving today.

Case study: bylaw blues

After careful thought, the board of a small co-op proposed revised and simplified bylaws that also included changes to the co-op’s capitalization strategy. Although the board wrote newsletter articles and publicized several informational meetings about the bylaws, no members came to the meetings. When the annual meeting was held, the board presented the bylaws and shared the work they had done. The board described the need to update and streamline the bylaws as the primary reason for the change—but as the board quickly realized, they had failed to anticipate their members’ response to the changes.

Some longtime members became angry when they for the first time took in the nature of the proposed changes and angrily and loudly voiced their concerns, and the meeting devolved into angry chaos. Opponents of the revised bylaws parked a car decorated with the words, “Vote NO” in front of the co-op for the monthlong balloting. And although the bylaws were approved, the board felt that it would be disruptive to implement the changes without further conversation. After a year of dialogue, newly revised bylaws were presented and approved by the members.

What worked? Board members and concerned co-op members contributed countless hours in meetings to rewrite the bylaws. By involving people with substantial history with the co-op as well as newer members, the bylaws took on a new face. But the board learned a valuable lesson as well: it had not understood what would concern its members—it had not listened to them well enough and/or communicated clearly enough a vision for the future as a vibrant, well-capitalized co-op effectively meeting the needs of its members and customers.

Learning together

What can we learn from these case studies? There are some important themes. One is that we can always do better. No matter how clearly we think we have communicated, there is always more to be done. Member linkage or owner engagement is not an abstract concept—rather, it is the way co-op leaders pay attention, so that we talk about the things that our owners are interested in and concerned about.

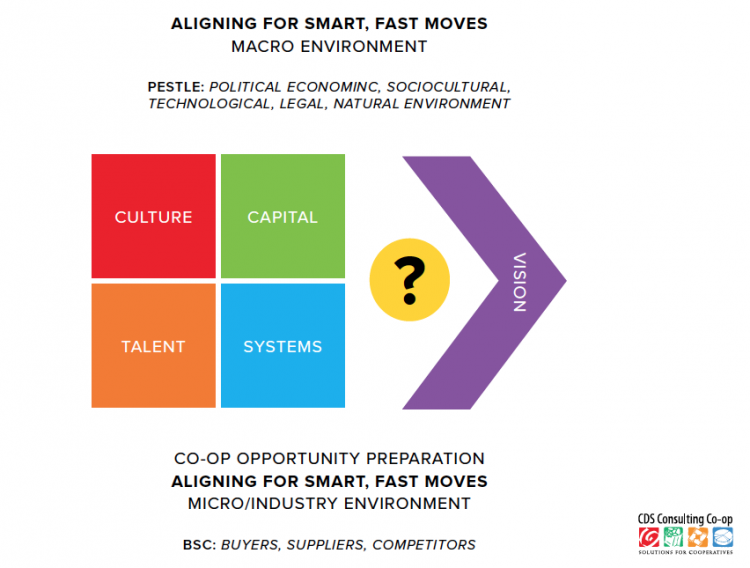

We also need to be sure that our co-ops are not “black boxes” to their members—that owners understand the things that are important to our cooperatives. What’s affecting our co-op? If we have a unionized staff, let’s all learn how the union works. If we have competition coming to town, let’s all learn what we offer as a co-op that makes the community stronger. If we know we need capital to grow and expand, let’s educate ourselves about capitalization strategies. (Check out the “Smart, Fast Moves” in the accompanying graphic for a way to organize our thinking to prepare for those conversations.)

Cultivate emotional literacy

We often celebrate that when cooperative members ask about the availability of a product, they use language like, “Do we have…”—indicating a personal investment in the cooperative. But this investment has a shadow side, in that sometimes, when members feel let down or disappointed by their cooperative, the anger that they can feel can be remarkably powerful and their expression of it particularly bitter. For board members, it’s important to recognize that the emotional investment that some individuals make in their cooperative is often more significant than the financial investment. Successful cooperation then, requires that we hear and integrate the wisdom of emotion.

As we are well aware, it’s not ever just one thing but rather a web of complex factors that reside at the core of our relationships and community that can cause a welling up of anger at the cooperative or spark that sense of betrayal. Our co-ops, even though they may have been successful over time, may have weaknesses that don’t easily show themselves. As cracks emerge, or as some co-ops move from thriving to merely surviving, can we find constructive ways to surface and talk about what might be a fundamental changes needed in our co-ops? How do we respect the diversity of thinking among members while at the same time providing leadership necessary for the future of the co- op?

Telling the whole story

In recent correspondence with a colleague new to cooperatives, he mused on the legacy culture of our retail food cooperatives as perhaps having to some degree a political system and reflective structure that is defined by itself, without reference to established business and professional norms. His thoughts remind me of the importance of understanding and intentionally shaping our co-op’s “legacy.” How well do you know the history of your co-op? Of your community? Cooperatives are a mirror of our communities, and as a result, we must take responsibility for the story that we tell about our co-ops. If our owners take us for granted, or fail to see the obstacles that we have surmounted and those we are now overcoming to persist and thrive, it might because we have not told the full story as we went along.

There has never been a greater need to tell a complete story, complex as it is. So many of our cooperatives grew out of a shared desire for self-reliance, to push back against an authoritarian and unresponsive food system, and in our triumph at our success we may have failed to take note of all of the small changes in the world that have happened since opening our store. In a world increasingly aware of the powerful social pressures affecting our governments and institutions, we as cooperators need to be aware of the way our culture continues to divide us.

Communicating through change

Systems, data, and strong leadership within the board are all valuable and necessary when a controversy erupts or communication within the co-op breaks down. We can cushion against the pain to some degree by continuing to listen to our owners, reflect on our strengths and weaknesses, and tell our story from every angle. But change is always disruptive, and whether it knocks at your co-op’s door in the form of angry or disappointed owners, or is part of a bold new strategy, the things that will carry the day are probably the softer attributes: curiosity, time, commitment, patience, openness. Perhaps most important are those board members who put in the extra effort and time to show up, to listen, to understand the co-op’s story, and to make sure that the co-op delivers on that story.

In all of the case studies here and in every controversy you might hear about, there were board members saying to themselves, “Wow—I didn’t know I signed up for THIS!” Yet they showed up, worked hard, and did their best. The most important thing we can all do to make our co-ops stronger is to bring our best selves forward in the work that we do: to be open, curious, respectful, civil and creative.

See you at the co-op!